Tutorial10: Shell Scripting - Part 1

Contents

[hide]INTRODUCTION TO SHELL SCRIPTING

Main Objectives of this Practice Tutorial

- Understand the process for planning prior to writing a shell script.

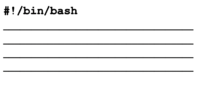

- Understand the purpose of a she-bang line contained at the top of a shell script.

- Setting permissions for a shell script and properly execute a shell script.

- Understand and use environment and user-defined variables within a shell script.

- Understand the purpose of control flow statements used with shell scripts.

- Use the test command to test various conditions.

- Use the if logic statement and the for loop statement within shell scripts.

Tutorial Reference Material

| Course Notes |

Linux Command/Shortcut Reference |

YouTube Videos | ||

| Course Notes:

|

Shell Scripting

Variables Commands |

Control Flow Statements | Brauer Instructional Videos: | |

KEY CONCEPTS

A shell script is a computer program designed to be run by the Unix shell, a command-line interpreter.

The various dialects of shell scripts are considered to be scripting languages.

Reference: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shell_script

Creating & Executing Shell Scripts

It is recommended to plan out on a piece of paper the purpose of the shell script.

You can do this by creating a simple IPSO diagram (stands for INPUT, PROCESSING, STORAGE, OUTPUT).

First, list the INPUTS into the script (eg. prompting user for data, reading data from file, etc), then listing the expected OUTPUTS from the script. You can then list the steps to process the INPUT to provide the OUTPUT (including file storage).

Once you have planned your shell script by listing the sequence of steps in your script, you need to create a file (using a text editor) that will contain your Linux commands.

NOTE: Avoid using filenames of already existing Linux Commands to avoid confusion. Using shell script filenames that include the file extension of the shell that the script will run within is recommended.

Using a Shebang Line

If you are learning Bash scripting by reading other people’s code you might have noticedthat the first line in the scripts starts with the #! characters and the path to the Bash interpreter.

This sequence of characters (#!) is called shebang and is used to tell the operating system

which interpreter to use to parse the rest of the file. Reference: https://linuxize.com/post/bash-shebang/

The shebang line must appear on the first line and at the beginning of the shell script,

otherwise, it will be treated as a regular comment and ignored.

Setting Permissions & Running a Shell Script

To run your shell script by name, you need to assign execute permissions for the user.

To run the shell script, you can execute it using a relative, absolute, or relative-to-home pathname

Example:

chmod u+x myscript.bash

./myscript.bash

/home/username/myscript.bash

~/myscript.bash

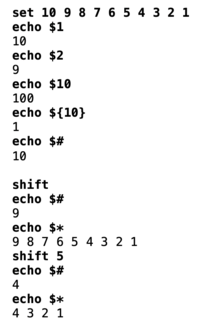

Using Variables in Shell Scripts

Definition

Variables are used to store information to be referenced and manipulated in a computer program.

They also provide a way of labeling data with a descriptive name, so our programs can be understood

more clearly by the reader and ourselves.

Reference: https://launchschool.com/books/ruby/read/variables

Environment Variables

(you can issue the pipeline command set | more to view all variables)

Placing a dollar sign ($) prior to the variable name will cause the variable to expand to the value contained in the variable.

User Defined Variables

User-defined variables are variables which can be created by the user and exist in the session. This means that no one can access user-defined variables that have been set by another user,

and when the session is closed these variables expire.

Reference: https://mariadb.com/kb/en/user-defined-variables/

Data can be stored and removed within a variable using an equal sign.

The read command can be used to prompt the user to enter data into a variable.

Refer to the diagram on the right-side to see how user-defined variables are assigned data.

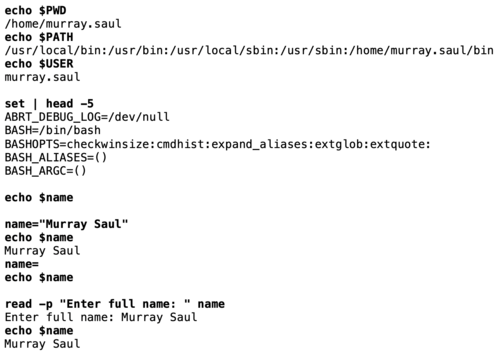

Positional Parameters and Special Parameters

A positional parameter is a variable within a shell program; its value is set from an argument specified on the command line that invokes the program.Positional parameters are numbered and are referred to with a preceding "$": $1, $2, $3, and so on. The positional parameter $0 refers to either the name of shell where command was issued, or name of shell script being executed. If using positional parameters greater than 9, then you need to include number within braces.

Examples: echo ${10}, ls ${23}

The shift command can be used with positional parameters to shift positional parameters

to the left by one or more positions.

There are a few ways to assign values as positional parameters:

- Use the set command with the values as argument after the set command

- Run a shell script containing arguments

There are a group of special parameters that can be used for shell scripting.

A few of these special parameters and their purpose are displayed below:

$* , “$*” , "$@" , $# , $?

Refer to the diagram to the right for examples using positional and special parameters.

Using Control Flow Statements in Shell Scripts

Control Flow Statement are used to make your shell scripts more flexible and can adapt to changing situations.

The special parameter $? Is used to determine the exit status of the previously issued Linux command. The exit status will either display a zero (representing TRUE) or a non-zero number (representing FALSE). This can be used to determined if a Linux command was correctly or incorrectly executed.

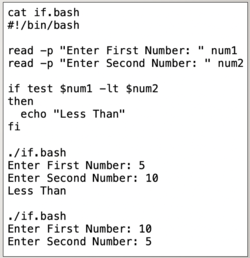

The test Linux command is used to test conditions to see if they are TRUE (i.e. value zero) or FALSE (i.e. value non-zero) so they can be used with control flow statements to control the sequence of a shell script.

You CANNOT use the > or < symbols when using the test command since these are redirection symbols. Instead, you need to use options when performing numerical comparisons. Refer to the table below for test options and their purposes.

There are other comparison options that can be used with the test command such as testing to see if a regular file or directory pathname exists, or if the regular file pathname is –non-empty.

Refer to diagrams to the right involving the test command.

Logic Statements

A logic statement is used to determine which Linux commands to be executed based

on the result of a condition (i.e. TRUE (zero value) or FALSE (non-zero value)).

There are several logic statements, but we will just concentrate on the if statement.

if test condition

then

command(s)

fi

Refer to the diagram relating to logic statements on the right side for an example.

Loop Statements

A loop statement is a series of steps or sequence of statements executed repeatedly zero or more times satisfying the given condition is satisfied.

Reference: https://www.chegg.com/homework-help/definitions/loop-statement-3

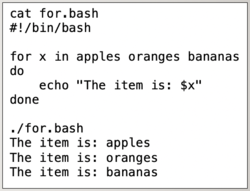

There are several loops, but we will look at the for loop using a list.

for item in list

do

command(s)

done

Refer to the diagram relating to looping statements on the right side for an example.

INVESTIGATION 1: CREATING A SHELL SCRIPT

In this section, you will learn how to create and run a simple Bash Shell script.

Perform the Following Steps:

- Login your matrix account.

- Issue a command to confirm you are located in your home directory.

We want to create a Bash Shell script to welcome the user by their username. Let's first provide some useful tips in terms

of selecting an appropriate name for the shell script. - Issue the following linux command to check if your intended shell script name

is already exists to be run automatically from the Bash shell:

which hello

You should notice that there is no output and therefore, this shell script name can be used.

On the other hand, if you wanted to create a file called sed, then the which sed command

would indicate it is already being used by the shell and that sed wouldn't be an appropriate shell script name to use. - Use a text editor like vi or nano to create the text file called hello (eg. vi hello)

If you are using the nano text editor, refer to notes on text editing in a previous week in the course schedule. - Enter the following two lines in your shell script, replacing "your-username" with your actual name:

clear

echo "Hello your-username" - Save your editing session and exit the text editor (eg. with vi: press ESC, then type :wx followed by ENTER).

- Issue the following linux command to run your shell script in your current directory:

./hello

You should notice an error indicating you don't have permissions to run the file.

You need to first add execute permissions prior to running the shell script. - Issue the following linux command to add execute permissions for your shell script:

chmod u+x hello - Re-run your shell script: ./hello

Although your shell script should work, it is recommended to force your shell script to run in a specific shell. This helps prevent your shell script encountering errors when run in the incorrect shell (i.e. syntax not recognized in a specific shell). - Edit your hello shell script using a text editor.

- Insert the following line at the beginning of the first line of your hello file:

#!/bin/bash

This is referred to as a she-bang line. It forces the script to be run in the Bash Shell. When your Bash Shell script finishes execution, you are returned to your current shell that you are using (which in our case in Matrix, is still the Bash shell). - Save your editing changes and exit your text editor.

- It is a good idea to rename your shell script to include an extension to indicate that the file is a Bash Shell script file. Issue the following linux command to rename your shell script file:

mv hello hello.bash - Run your renamed shell script by issuing:

./hello.bash

- In the next investigation, you will learn to create and run shell scripts that

use variables, positional and special parameters.

- In the next investigation, you will learn to create and run shell scripts that

INVESTIGATION 2: USING VARIABLES IN SHELL SCRIPTS

In this section, you will learn how to use variables, positional and special parameters to assist you in creating adaptable shell scripts.

Perform the Following Steps:

- Use a text editor to edit the shell script called hello.bash

- Add the following line to the bottom of the file:

echo "The current shell you are using is: $SHELL" - Save your editing changes and exit your text editor.

- Issue the following linux command to change to the Bourne Shell (a different shell than the default Bash):

sh - Issue the following linux command to confirm you are in the Bourne Shell:

echo $SHELL

You should see the output of the command that you are located in the Bourne Shell. - Run your hello.bash shell script.

What shell does the shell script indicate is running?

This is because of the shebang line indicating to run the shell script in the Bash shell although you ran this script within the Bourne Shell. - Enter the following linux command to return to your Bash shell: exit

- Use a text editor to edit the shell script called hello.bash

- Add the following lines to the bottom of the file:

echo "The current username is: $USER"

echo "The current directory location is: $PWD"

echo "The current user's home directory is: $HOME - Save your editing changes and exit your text editor.

- Run your hello.bash shell script.

Take time to view the output and the values of the environment variables. - Issue the following linux command to add your current directory to the PATH environment variable:

PATH=$PATH:. - Issue the following linux command to confirm that the current directory "." has been added to the PATH environment variable:

echo $PATH - Run the hello.bash by just shell script name (i.e. to not use ./ prior to shell script name).

The shell script should run just by name. - Exit your Matrix session, and log back into your Matrix session.

- Re-run the hello.bash shell script by just using the name.

What did you notice?

The setting of the PATH variable only worked in the current session only. If exit the current Matrix session, then the recently changed settings for environment variables are lost. You will learned in Week 12 how to set environment variables in startup files. - Use a text editor to create a file called user-variables.bash

- Add the following lines to the bottom of the file:

#!/bin/bash

age=25

readonly age

read -p "Enter your Full Name" name

read -p "Enter your age (in years): " age

echo "Hello $name - You are $age years old" - Save your editing changes and exit your text editor.

- Issue the chmod command to add execute permissions for the user for the user-variables.bash file.

- Issue the following to run the user-variables.bash Bash shell script:

./user-variables.bash

What do you notice when you try to change the age variable? Why? - Use a text editor to create a file called parameters.bash

- Add the following lines to the bottom of the file:

#!/bin/bash

echo \$0: $0

echo \$2: $2

echo \$3: $3

echo \$#: $#

echo \$*: $*

shift 2

echo \$#: $#

echo \$*: $* - Save your editing changes and exit your text editor.

- Issue the chmod command to add execute permissions for the user for the parameters.bash file.

- Issue the following to run the user-variables.bash Bash shell script:

./parameters.bash

What happened?

The values for the parameters may not be displayed properly since you did NOT provide any arguments when running the shell script. - Issue the following to run the user-variables.bash Bash shell script with arguments:

./parameters.bash 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Take some time to view the results and how the parameters are changed when using the shift command. What do you notice?

In the next investigation, you will use control-flow statements to allow your shell scripts to perform differently under different situations.

INVESTIGATION 3: USING CONTROL FLOW STATEMENTS IN SHELL SCRIPTS

In this section, you will learn how to use control-flow statements to make your shell script behave differently under different situation.

Perform the Following Steps:

- Before learning about logic and loop control-flow statements, you need to first learn about issuing test conditions using the test command.

- Issue the following linux commands to assign values to several variables:

course="ULI101"

number1=5

number2=10 - Issue the following linux command to test a condition:

test $course = "ULI101"

The $? variable is used to store an exit status of the previously command issued (including the test command). If the status is zero, then it indicates a TRUE value and if the status is non-zero, then it indicates a FALSE value. - Issue the following linux command to view the status of the previously-issued test command:

echo $?

Based on its value, is the result TRUE or FALSE? - Issue the following linux command to test another condition:

test $course = "uli101" - Issue the following linux command to view the status of the previously-issued test command:

echo $?

The value is non-zero (FALSE) since UPPERCASE characters are different than lowercase characters. - Issue the following linux command to test another condition:

test $course != "uli101" - Issue a linux command to display the value of $?. What is the result? Why?

- Issue the following linux command to test a condition involving numbers:

test $number1 > $number2 - Issue a linux command to display the value of $?. NOTE: You will notice that something is wrong.

The exit status $? shows a zero (TRUE) value, but the number 5 is definitely NOT greater than 10.

The problem is that the symbols < and > are interpreted as REDIRECTION symbols! - To prove this, issue the following linux command :

ls 10

You should notice a file called "10". The incorrectly issued test command used redirect to create an empty file instead,

which indeed succeeded just giving a TRUE value!

To prevent these incorrectly issued testing for number comparison, you can use the following options instead:

-lt (<), -le (<=), -gt (>), -ge (>=;), -eq (=), -ne (!=) - Issue the correct linux command to properly test both values:

test $number1 -gt $number2 - Issue a linux command to display the value of $?. You should notice that the exit status value is now FALSE which is the correct result.

- The test command can be abbreviated by the square brackets [ ] which contain the test condition within the square brackets. You need to have spaces between the brackets and the test condition; otherwise, you will get a test error.

- To generate a test error, issue the improper use of the test command:

[$number1 -gt $number2]

You should notice an test error message. - Issue the correct use of the test command:

[ $number1 -gt $number2 ]

Issue a command to view the value of the exit status of the previously issued test command. You should notice that is works properly.

LINUX PRACTICE QUESTIONS

The purpose of this section is to obtain extra practice to help with quizzes, your midterm, and your final exam.

Here is a link to the MS Word Document of ALL of the questions displayed below but with extra room to answer on the document to simulate a quiz:

https://ict.senecacollege.ca/~murray.saul/uli101/uli101_week10_practice.docx

Your instructor may take-up these questions during class. It is up to the student to attend classes in order to obtain the answers to the following questions. Your instructor will NOT provide these answers in any other form (eg. e-mail, etc).

Review Questions:

PART A: WRITE BASH SHELL SCRIPT CODE

Write the answer to each question below the question in the space provided.

- Write a Bash shell script that clears the screen and displays the text Hello World on the screen.

What permissions are required to run this Bash shell script?

What are the different ways that you can run this Bash shell script from the command line? - Write a Bash shell script that clears the screen, prompts the user for their full name and then prompts the user for their age,

then clears the screen again and welcomes the user by their name and tells them their age.

What comments would you add to the above script’s contents to properly document this Bash shell script to be understood

for those users that would read / edit this Bash shell script’s contents? - Write a Bash shell script that will first set the value of a variable called number to 23 and make this variable read-only.

Then the script will clear the screen and prompt the user to enter a value for that variable called number to another value.

Have the script display the value of the variable called number to prove that it is a read-only variable.

When you ran this Bash shell script, did you encounter an error message?

How would you run this Bash shell script, so the error message was NOT displayed? - Write a Bash shell script that will clear the screen and then display all arguments that were entered after your Bash shell script when it was run. Also have the Bash shell script display the number of arguments that were entered after your Bash shell script.

PART B: WALK-THRUS

Write the expected output from running each of the following Bash shell scripts You can assume that these Bash shell script files have execute permissions. Show your work.

- Walkthru #1:

- cat walkthru1.bash

#!/usr/bin/bash word1=”counter” word2=”clockwise” echo “The combined word is: $word2$word1”

- WRITE OUTPUT FROM ISSUING:

- ./walkthru1.bash

- Walkthru #2:

- cat walkthru2.bash

#!/usr/bin/bash echo “result1: $1” echo “result2: $2” echo “result3: $3” echo “result 4:” echo “$*”

- WRITE OUTPUT FROM ISSUING:

- ./walkthru2.bash apple orange banana