Difference between revisions of "GPU621/Group 1"

Pujakakani (talk | contribs) (→Solution) |

Pujakakani (talk | contribs) (→Solution) |

||

| Line 185: | Line 185: | ||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

| − | |||

#include <iostream> | #include <iostream> | ||

#include <thread> | #include <thread> | ||

| Line 261: | Line 260: | ||

return 0; | return 0; | ||

} | } | ||

| − | |||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

Revision as of 18:46, 9 April 2023

Contents

Analyzing False Sharing

Team Members

Introduction : What is False Sharing?

Multicore programming is important to take advantage of the hardware's power as multicore processors are more common than ever. This is because it enables us to run our code on various CPU cores. But in order to effectively utilise it, it is crucial to know and comprehend the underlying hardware. The cache is one of the most crucial system tools. The majority of designs also have shared cache lines. And for this reason, false sharing in multicore/multithreaded tasks is a well-known issue. What is cache line ping-ponging, also known as false sharing? When multiple threads exchange data, one of the sharing patterns that has an impact on performance is false sharing. It occurs when at least two threads alter or use data that is in near proximity to one another in memory.

When multiple threads exchange data, one of the sharing patterns that has an impact on performance is false sharing. When at least two threads change or use data that just so happens to be nearby in memory and ends up in the same cache line, it causes this problem. False sharing happens when they frequently change their individual data in such a way that the cache line switches back and forth between the caches of two different threads.

Cache

In order to boost system performance, a cache is a high-speed data storage layer that stores frequently accessed or recently used data. By retaining a copy of the most often visited data in a quicker and more convenient storage location, it is intended to decrease the amount of time it takes to access data.

Web servers, databases, operating systems, and CPUs are just a few of the systems that utilise caches. Caching, for instance, enables web servers to keep frequently requested web pages in memory and speed up serving them to consumers. To cut down on the time it takes to access frequently used instructions and data from main memory, CPUs store them in caches.

Caching can enhance system performance by lowering the number of time-consuming or expensive actions needed to access data. If the cached data is not updated when changes are made to the underlying data source, caching also raises the chance of stale data. Cache management and eviction tactics are crucial factors to take into account when building caching systems as a result.

Cache Consistency

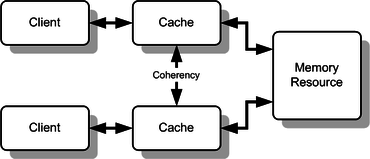

Cache consistency refers to the synchronization of data between different caches in a computer system, ensuring that all caches have the most up-to-date version of data. In a multi-core processor or a distributed computing system, multiple processors may have their own local caches that store a copy of the data that is being used by the processor.

Each processor in a Symmetric Multiprocessor (SMP)system has a local cache. The local cache is a smaller, faster memory that stores data copies from frequently accessed main memory locations. Cache lines are closer to the CPU than main memory and are designed to improve memory access efficiency. In a shared memory multiprocessor system with a separate cache memory for each processor, shared data can have multiple copies: one in main memory and one in the local cache of each processor that requested it. When one of the data copies is modified, the other copies must also be modified. Cache coherence is the discipline that ensures that changes in the values of shared operands (data) are propagated in a timely manner throughout the system. Multiprocessor-capable Intel processors use the MESI (Modified/Exclusive/Shared/Invalid) protocol to ensure data consistency across multiple caches.

Cache consistency is important because without it, different processors may have different versions of the same data, which can lead to data inconsistencies and errors in the system. Different cache consistency protocols, such as MESI and MOESI, are used to maintain cache consistency in modern computer systems. These protocols define a set of rules and states for cache coherence and ensure that all caches in the system have the same view of the shared memory.

The MESI protocol

One of the most widely used cache coherence algorithms is the MESI protocol.

MESI (short for Modified, Exclusive, Shared, Invalid) consists of 4 states.

Modified - The only cached duplicate is the modified, distinct from main memory cache line.

Exclusive - The modified, separate from main memory cache line is the only cached copy.

Shared - identical to main memory, but there might be duplicates in other caches.

Invalid - Line data is not valid.

How does it work?

Let's say 2 cores (core 1 and core 2) are close to each other physically and are receiving memory from the same cache line. They are reading long values from main memory (value 1 and value 2).

core 1 is reading value 1 from main memory. It will proceed to fetch values from memory and store them into the cache line.

Once that is done it will mark that cache line as as exclusive because core 1 is the only core operating in the cache line.

For efficiency this core will now read the stored cache value instead of reading the same value from memory when possible this will save time and processing power.

core 2 also starts to read values but from value 2 from the main memory.

Due to core 2 being in the same cache line as core 1 both cores will tag their cache lines as shared.

If core 2 decides to modify the value of 1. It modifies its value in local cache and changes its state from shared to modified

Lastly. core 2 notifies core 1 of the changes in values. which marks the cache line as invalid.

Example

In this example, we have two threads running in parallel, each incrementing a separate counter variable. The volatile keyword is used to ensure that the compiler doesn't optimize away the increments. We also define the cache line size as 64 bytes.

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <chrono>

using namespace std;

using namespace chrono;

// Constants to control the program

const int NUM_THREADS = 2;

const int NUM_ITERATIONS = 100000000;

const int CACHE_LINE_SIZE = 64;

// Define a counter struct to ensure cache line alignment

struct alignas(CACHE_LINE_SIZE) Counter {

volatile long long value; // the counter value

char padding[CACHE_LINE_SIZE - sizeof(long long)]; // padding to align the struct to cache line size

};

// Define two counter variables

Counter counter1, counter2;

// Function to increment counter 1

void increment1() {

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_ITERATIONS; i++) {

counter1.value++;

}

}

// Function to increment counter 2

void increment2() {

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_ITERATIONS; i++) {

counter2.value++;

}

}

// Function to check the runtime of the program

void checkRuntime(high_resolution_clock::time_point start_time, high_resolution_clock::time_point end_time) {

auto duration = duration_cast<milliseconds>(end_time - start_time).count();

cout << "Runtime: " << duration << " ms" << endl;

}

int main() {

// Print the cache line size

cout << "Cache line size: " << CACHE_LINE_SIZE << " bytes" << endl;

// Run the program using a single thread

cout << "Running program using a single thread" << endl;

high_resolution_clock::time_point start_time = high_resolution_clock::now();

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_ITERATIONS; i++) {

counter1.value++;

counter2.value++;

}

high_resolution_clock::time_point end_time = high_resolution_clock::now();

checkRuntime(start_time, end_time);

cout << "Counter 1: " << counter1.value << endl;

cout << "Counter 2: " << counter2.value << endl;

// Run the program using multiple threads

cout << "Running program using " << NUM_THREADS << " threads" << endl;

counter1.value = 0;

counter2.value = 0;

start_time = high_resolution_clock::now();

thread t1(increment1);

thread t2(increment2);

t1.join();

t2.join();

end_time = high_resolution_clock::now();

checkRuntime(start_time, end_time);

cout << "Counter 1: " << counter1.value << endl;

cout << "Counter 2: " << counter2.value << endl;

return 0;

}

In this example we have provided we provided a single thread and a multi thread solution.

Based on results the single thread solution runs faster then the multi thread. But why?

The reason for this is the synchronization and cache invalidation overheads cause the slower execution time for the multi-threaded solution. Despite the execution being split between 2 threads.

Although if the number of iterations is increased. At some point running the solution in serial will cause it to run slower then the multi threaded solution. Why is so?

By increasing the NUM_ITERATIONS it causes the serial solution to run slower because the loop in in the serial solution is excecated sequentially.

As a result more work is being applied on the thread which causes it to bottleneck.

Meanwhile the multi threaded solution does not cause a bottle neck because the work is split between 2 threads allowing them to work on less iterations at the same time. As a result it decreases the amount of time it takes to run through those iterations.

Solution

When two threads update different variables that share the same cache line, this is known as false sharing. A performance hit results as a result of each thread invalidating the cache line for the other thread. In order to ensure that each variable is aligned to its own cache line, we can fix this issue by adding padding to the Counter struct. By ensuring that each thread updates a different cache line, false sharing is prevented.

We can further optimize the code by switching to atomic variables from volatile variables, which solves the issue of false sharing as well. In order to ensure that the variables are updated atomically, atomic variables offer a higher level of synchronization.

The updated code, which addresses false sharing and optimization, is provided below:

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <chrono>

#include <atomic>

using namespace std;

using namespace chrono;

// Constants to control the program

const int NUM_THREADS = 2;

const int NUM_ITERATIONS = 100000000;

const int CACHE_LINE_SIZE = 64;

// Define a counter struct with padding for cache line alignment

struct alignas(CACHE_LINE_SIZE) Counter {

atomic<long long> value; // the counter value

char padding[CACHE_LINE_SIZE - sizeof(atomic<long long>)]; // padding to align the struct to cache line size

};

// Define two counter variables

Counter counter1, counter2;

// Function to increment counter 1

void increment1() {

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_ITERATIONS; i++) {

counter1.value++;

}

}

// Function to increment counter 2

void increment2() {

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_ITERATIONS; i++) {

counter2.value++;

}

}

// Function to check the runtime of the program

void checkRuntime(high_resolution_clock::time_point start_time, high_resolution_clock::time_point end_time) {

auto duration = duration_cast<milliseconds>(end_time - start_time).count();

cout << "Runtime: " << duration << " ms" << endl;

}

int main() {

// Print the cache line size

cout << "Cache line size: " << CACHE_LINE_SIZE << " bytes" << endl;

// Run the program using a single thread

cout << "Running program using a single thread" << endl;

high_resolution_clock::time_point start_time = high_resolution_clock::now();

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_ITERATIONS; i++) {

counter1.value++;

counter2.value++;

}

high_resolution_clock::time_point end_time = high_resolution_clock::now();

checkRuntime(start_time, end_time);

cout << "Counter 1: " << counter1.value << endl;

cout << "Counter 2: " << counter2.value << endl;

// Run the program using multiple threads

cout << "Running program using " << NUM_THREADS << " threads" << endl;

counter1.value = 0;

counter2.value = 0;

start_time = high_resolution_clock::now();

thread t1(increment1);

thread t2(increment2);

t1.join();

t2.join();

end_time = high_resolution_clock::now();

checkRuntime(start_time, end_time);

cout << "Counter 1: " << counter1.value << endl;

cout << "Counter 2: " << counter2.value << endl;

return 0;

}

Sources

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/archive/msdn-magazine/2008/october/net-matters-false-sharing

http://www.nic.uoregon.edu/~khuck/ts/acumem-report/manual_html/multithreading_problems.html

https://levelup.gitconnected.com/false-sharing-the-lesser-known-performance-killer-bbb6c1354f07

https://www.easytechjunkie.com/what-is-false-sharing.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cache_coherence

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/computer-science/cache-consistency

https://wiki.cdot.senecacollege.ca/wiki/Team_False_Sharing

https://www.cs.utexas.edu/~pingali/CS377P/2018sp/lectures/mesi.pdf